Background

Collision Avoidance (COLAV) for autonomous ships relies on the prediction of the future motion of nearby vessels or obstacles, as this is important for having sufficient situational awareness and making intelligent decisions. Some COLAV methods have a significant amount of tuning parameters [4], [1], [5], where several of these parameters in reality depend on the obstacles faced in hazardous situations and their intentions [7]. Thus, it would be beneficial in terms of reducing the tuning complexity and increase the method robustness, to have an estimator which can update selected obstacle dependent parameters using historical Automatic Identification System (AIS) data from relevant nearby vessels or obstacles. The AIS data is sent from most commercial vessels, which transmits information about their position, course, speed, turn rate, identification number, possibly end destination information and so on.

Data from several ferries or vessels in the Trondheimsfjord can be obtained and used, with some examples shown in the Figure below. Relevant AIS data for these vessels can then be used for learning or estimation purposes. Project proposals employing AIS data from these (or possibly also other vessels) are given in the next sections.

|

|

|

| Local vessels operating in the Trondheimsfjord. From top left to bottom right going left to right: Trondheimsfjord 1 & 2, Korsfjord and Glutra. |

Learn a Bayesian network for obstacle intent inference

The Probabilistic Scenario-based Model Predictive Control (PSB-MPC) in [7] can utilize intention information of nearby obstacles in order to make decisions with increased safety margins and/or efficiency. However, work is still needed to establish a module for infering the intention of nearby obstacles. It would therefore be of great benefit to create a module which uses AIS data and/or vessel-to-vessel communication to update intent information for use in the COLAV system. The module can then for instance also have estimated offline to what degree the obstacle will adhere to the maritime traffic rules (COLREGS) [3], which is valuable information to consider when choosing what avoidance maneuver to use in a proactive COLAV system.

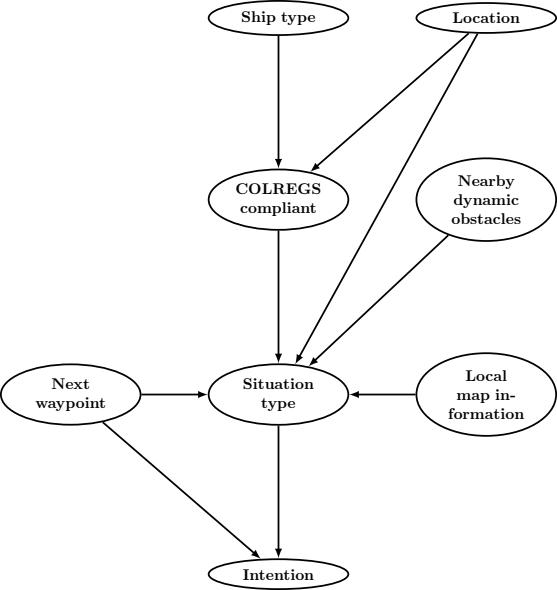

Here, Bayesian networks are a conveinent way of representing the dependencies for obstacle intention, and several methods exist for learning such networks [2], depending on whether the network structure is given or not. An example Bayesian net for obstacle intention inference is given in the Figure below.

|

| Example Bayesian net for intention inference for an obstacle ship, considering seven factors (topmost nodes). The situation type is here either overtaking, head-on or crossing, and whether or not the obstacle is stand-on |

| or give-way vessel. Definitions of these situations can be found in [3]. Nearby dynamic obstacles can e.g. be represented by a list containing data structures carrying data on their states [7]. |

The suggested tasks for this project thesis are to

- Perform a literature survey on methods for learning Bayesian networks

- Suggest a Bayesian network structure for obstacle intention inference

- Generate AIS data in simulation or use real world datasets from vessels in the Trondheimsfjord, preprocess and partition into training and test data for use in Bayesian network learning

- There are two options here: 1) Learn the parameters (conditional probabilities) of the proposed Bayesian network using the simulated/real data, or 2) Learn both its structure and parameters using the data. Different methods are here applicable for the parameter learning task, with Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation, bayesian inference, variational inference, Expectation Maximization (EM) to mention a few. When it comes to also learning the structure, several methods exist.

- Validate the resulting network in simulation on test data, for each vessel considered.

Estimate Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process parameters for an obstacle prediction model

The Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) process is a stochastic process originally applied to model the Brownian motion of a particle under friction [8]. Compared to Wiener motion (random walk) which can drift off its initial state, the OU process has a tendency to revert back towards its mean. This is a reasonable assumption for many vessels in traffic, as they will most likely keep a constant speed in transit, close to their max speed or cruising speed. In recent times, the model has been used in the long-term prediction of vessel motion [5], [6] using AIS data, and also in COLAV [7]. Because of its revertion tendency, the model has the ability to predict over larger time scales without exploding the associated uncertainty, as can occur when using a Constant Velocity (CV) model.

The suggested tasks for this project are to

- Perform a literature survey on long-term vessel prediction methods

- Generate AIS data in simulation or use real world datasets from vessels in the Trondheimsfjord, preprocess and partition into training and test data for use in OU parameter estimation

- Implement the OU model for vessel motion (position and velocity).

- Implement an offline and/or online OU parameter estimator, and use to estimate the OU parameters for each vessel using the training data. Different methods can here be applied.

- Validate the resulting OU model for each vessel on the test data.

Extension into a Master’s thesis

Both projects can be extended into a Master’s thesis, where the results are integrated and tested for use in an existing COLAV method.

References

[1] Eriksen, B.-O. H., Bitar, G. I., Breivik, M., and Lekkas, A. M., “Hybrid collision avoidance for ASVs compliant with COLREGs rules 8 and 13-17” ArXiv, vol. abs/1907.00198, 2019.

[2] Heckerman, D., “A tutorial on learning with bayesian networks” Studies in Computational Intelligence, pp 33-82, 2020.

[3] IMO, “COLREGS - International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea” Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, 1972, 1972.

[4] Johansen, T. A., Perez, T., and Cristofaro, A., “Ship collision avoidance and COLREGS compliance using simulation-based control behavior selection with predictive hazard assessment” IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, vol. 17, no. 12, pp. 3407-3422, Dec. 2016.

[5] Mazzarella, F., Arguedas, V. F., and Vespe, M., “Knowledge-based vessel position prediction using historical ais data” in Proc. Applications (SDF) 2015 Sensor Data Fusion: Trends, Solutions, Oct. 2015, pp. 1-6.

[6] Millefiori, L. M., Braca, P., Bryan, K., and Willett, P., “Long-term vessel kinematics prediction exploiting mean-reverting processes” in 2016 19th International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION), Jul. 2016, pp. 232-239.

[7] Tengesdal, T., Johansen, T. A., and Brekke, E. (2020). “Risk-based Maritime Autonomous Collision Avoidance Considering Obstacle Intentions.” in 2020 23rd International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION), South Africa, in press.

[8] Uhlenbeck, G. E. and Ornstein, L. S., “On the theory of the brownian motion”, Phys. Rev., vol. 36, pp. 823-841, 5 Sep. 1930.

Contact

Supervisors: Edmund Brekke and Trym Tengesdal